以心伝心 (ishindenshin) is a Japanese popular saying among Japanese. Its kanji characters literally means "similar minds/hearts, transmission to minds/hearts". The meaning of this saying is to communicate with each other's hearts/minds without using letters or words. In Zen Buddhism, it means to convey the essence of Buddhism, which is not expressed in words or letters, from the monk to the hearts of the disciples. There is even a game for kids with this name mostly played at school's sports day where a few people (usually five to ten people) tie both of their feet to each other and race with other groups. The key is to really synchronize with your team mates as accurate and as fast as you can. I remember playing this game as a kid, often falling and having a bleeding knee. It was fun and rewarding when it worked but but also painful because if someone were to fall down, the rest of the team mates would fall too ending up with their hands, elbows and knees bleeding.

I think ishindenshin is not painful only as a game, I think the real ishindenshin in Japan's daily life can be exclusive and upsetting for many too.

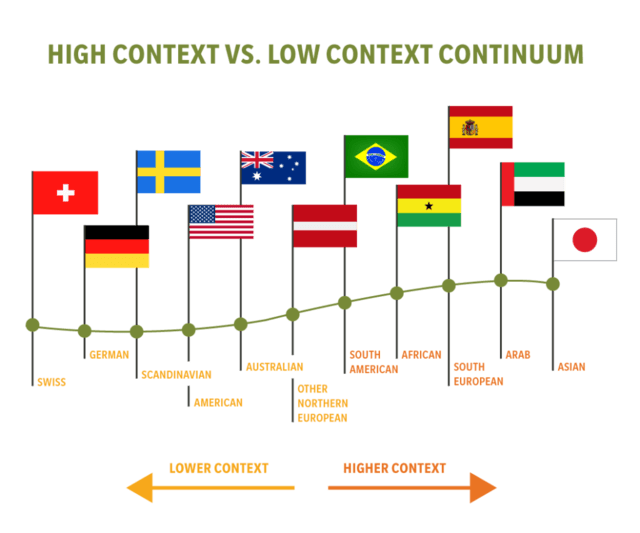

One can say Ishindenshin is one of the evidences or representation of what makes Japan have a high context culture. This means all Japanese has a shared common sense and therefore Japanese know what to expect from others and what to be expected by him/herself in social situations. Words and meaning don't necessarily (actually most of the time) go together in Japan. This is why it is important to learn about the culture and manners before visiting Japan. For example, in a inter-personal level, you need to be really good at reading between the lines. Japanese never really tell you directly what is on their minds. This is why you need to read in between the lines in a conversation and understand them. If you ask a Japanese friend to hangout, he/she might say ummm idk if I should go..., It's a little late to go out... Your friend might not say NO even if they don't really want to go out with you because that is rude and he/she might even say yes putting a smile on the face. This is why you have to read between the lines and see if your friend is tired or if he/she has to wake up early for work the next day. so you can take the right actions. While no means no and yes means yes in many countries, it is more complicated to understand the meaning of things Japanese communicate with you.

In a social level, it can be hard for some foreigners to know what they are "supposed" to do and don't anger Japanese. The other day, I was in the train and I think it was an Indian woman that was talking on the phone in her language. She was pretty quiet and thoughtful not to speak too loud on the phone. Inside of the train was much louder as people were talking and the train running itself was loud. However, the old couple and a few other Japanese people were staring at her angrily (Japanese hardly ever stare at you especially in public, let alone angrily) as if she was committing a crime and as if she was being the loudest person in the train. I felt bad for her because while it is not a legal law for you not to talk on the phone in trains, Japanese take it very seriously. It makes sense that people should respect and be quiet in trains but the train was already pretty loud and other people were talking so it was frustrating to see Japanese be bothered by her.

This was just a small example of what it can happen with Japanese ishindenshin. It can be good for Japanese to unite and understand each other but a high context culture can be confusing and frustrtaing for many. I'd say it is especially hard for foreigners to understand ishindenshin and feel included even if they learned how to speak Japanese properly. Like the game ishindenshin for kids, you can appreciate this admirable communication style where a whole country has a bond and a facility to understand each other but people can also get hurt sometimes by making mistakes and being judged by Japanese society.