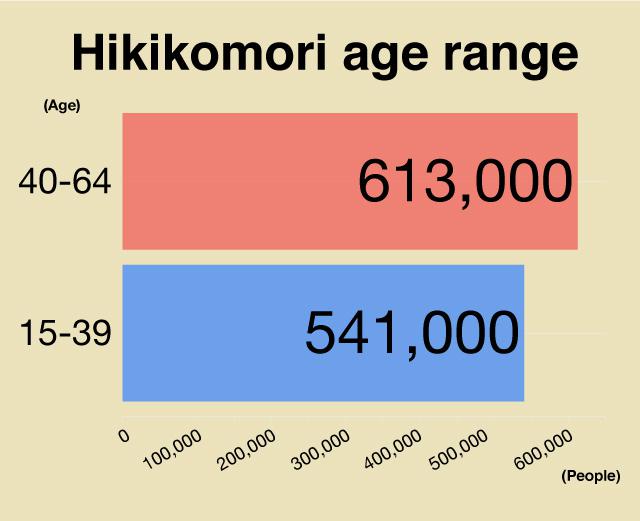

A survey conducted by Japan's Cabinet Office in 2015, found that an estimated 541,000 people between 15 and 39 were hikikomori. But a similar survey done by Cabinet Office carried out in December of 2018, found that an estimated 613,000 people between 40 and 64 also fell into the category. It was the first time this age range was surveyed, leaving a surprising number surpassing the 15 to 39 range which hikikomori are typically thought to fall in.

Here is where the "8050 problem" relies. This name stems from the situation in which parents in their 80s support hikikomori children in their 50s.

The Cabinet Office survey shows that 75 percent of hikikomori between 40 and 64 are men and that about 21% say they have lived this way for 3 to 5 years. Overall, more than 50 percent say they have been Hikikomori for 5 years or longer. Some have even lived this way for 30 years or longer. 34.1% said answered "both parents" are main income source for them.

Morito Ishizaki editor-in-chief of HIKIPOS magazine says the 8050 problem is happening because a lot of people who joined the workforce during Japan's period of high economic growth have quit and remained jobless. He thinks these people are unable to find a purpose in life other than work and have become "socially isolated" at home as a result. He says, young Hikikomori still might think they have a brighter future and that things might change one day but for Hikikomori in their 50s, it is hard to think they will do any better.

The truth about Japan's Hikikomori explains in detail how Hikikomori become a Hikikomori.(watch)

Seems, the environment in which a child grow up in has a lot to do with how one become a Hikikomori. Some grew up being bullied, some had really strict parents, others have mental illness since they were born, some are LGBT and the list goes on and on.

Work in Japan can also be a toxic environment for those who are more sensitive. Japan, where especially over work is a culture, people tend to only go to work and home, home and work. People are afraid of failing or not being good enough for a compony or their own family they end up putting too much pressure on themselves.

Although, 95% of Hikikomori show some mental illness or disorder, going to counseling and therapy is still a taboo in Japan as Japanese society still discriminate those who openly say they seek for help at therapy. Because of this, it is said people are 40 times less likely to go counseling in Japan compared to the US. Furthermore, often health insurance cover counseling or mental health in the US whereas in Japan that doesn't happen at all so it is expensive to seek help.

Ishizaki says it would be a good idea for the community to give more support to the elderly parents who take care of their Hikikomori children in their 50s. Because the reality is that a lot of Hikikomori want to help their parents and feel sorry for what they make them go through.

Jiro Ito an NPO psychiatrist says it is possible to impact and make positive changes in a Hikikomori life by working on therapy and counseling. He say 30% to 40% are able to live a happier life after therapy.

Ryosuke Hoshino who used to be a Hikikomori says one day there should be a Japanese society where it is obvious to go to therapy. He says people should go to therapy just like when they go to see the doctor when they catch a cold.

Hikikomori has been a Japanese social problem for a while now and it has not gotten any better by leaving it alone, it is time for the government to get more involved making it easier for people with mental illness to have access to professional help. We can only hope that changes will be made and help friends in need if they need to talk or get some burden off of their shoulders.